From Chestnut Street north went

that road of our childhood,

Fascinating all the way

From the tavern owned by one

classmate’s folks,

Past a couple of factories

Fish market, shoemaker’s shop,

hardware, grocery stores, laundry,

And a drug store with several

large, shining globes,

Filled with liquid—red, yellow,

green, blue—

And the candy stores where a

penny bought

Lafayettes, lollipops, licorice, or

Mary Jane,

Or even a grab-bag of assorted

Sweet, crunchy, chewy morsels,

Or a nickel bar of brown or pink or white taffy;

And on through Chinatown

Where restaurants served strange foods,

To the markets which

We could only visit on Saturdays.

The Markets! outdoor extravaganzas

Of meats, eggs, produce, fish, bread,

And, wondrous bright,

A great revolving cylinder

roasting peanuts—

What a smell! and what a taste!

Hot peanuts, m-m-m, delicious!

Oh! what an adventure a

trip to the markets—

of Mulberry Street was!

Through busy crowds of people all intent,

And maybe bumping us about,

But it did not bother us.

The joy of being in the

middle of it all

Went home with us to

be savored

Till we went that way again.

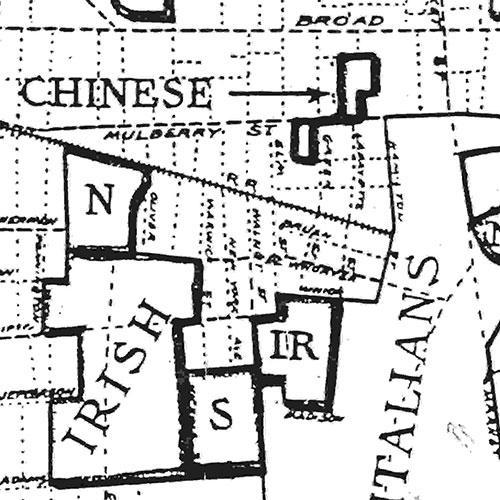

Alma Flagg’s trip up “old Mulberry Street” can be traced (in reverse order) through the listings in Price & Lee’s 1940 Newark city directory, of which a small section is shown here. The poem is found in Flagg’s collection Lines, colors, and more (1998).