In those days, those days which exist for me only as the most elusive memory now,

when often the first sound you’d hear in the morning would be a storm of birdsong,

then the soft clop of the hooves of the horse hauling a milk wagon down your block

and the last sound at night as likely as not would be your father pulling up in his car,

having worked late again, always late, and going heavily down to the cellar, to the furnace,

to shake out the ashes and damp the draft before he came upstairs to fall into bed;

in those long-ago days, women, my mother, my friends’ mothers, our neighbors,

all the women I knew, wore, often much of the day, what were called “housedresses,”

cheap, printed, pulpy, seemingly purposefully shapeless light cotton shifts,

that you wore over your nightgown, and, when you had to go to look for a child,

hang wash on the line, or run down to the grocery store on the corner, under a coat,

the twisted hem of the nightgown, always lank and yellowed, dangling beneath.

More than the curlers some of the women seemed constantly to have in their hair,

in preparation for some great event, a ball, one would think, that never came to pass;

more than the way most women’s faces not only were never made up during the day,

but seemed scraped, bleached, and, with their plucked eyebrows, scarily masklike;

more than all that it was those dresses that made women so unknowable and forbidding,

adepts of enigmas to which men could have no access, and boys no conception.

Only later would I see the dresses also as a proclamation: that in your dim kitchen,

your laundry, your bleak concrete yard, what you revealed of yourself was a fabulation;

your real sensual nature, veiled in those sexless vestments, was utterly your dominion.

In those days, one hid much else, as well: grown men didn’t embrace one another,

unless someone had died, and not always then; you shook hands, or, at a ball game,

thumped your friend’s back and exchanged blows meant to be codes for affection;

once out of childhood you’d never again know the shock of your father’s whiskers

on your cheek, not until mores at last had evolved, and you could hug another man,

then hold on for a moment, then even kiss (your father’s bristles white and stiff now).

What release finally, the embrace: though we were wary–it seemed so audacious–

how much unspoken joy there was in that affirmation of equality and communion,

no matter how much misunderstanding and pain had passed between you by then.

We knew so little in those days, as little as now, I suppose, about healing those hurts:

even the women, in their best dresses, with beads and sequins sewn on the bodices,

even in lipstick and mascara, their hair aflow, could only stand wringing their hands,

begging for peace, while father and son, like thugs, like thieves, like Romans,

simmered and hissed and hated, inflicting sorrows that endured, the worst anyway,

through the kiss and embrace, bleeding from brother to brother into the generations.

In those days there was still countryside close to the city, farms, cornfields, cows;

even not far from our building with its blurred brick and long shadowy hallway

you could find tracts with hills and trees you could pretend were mountains and forests.

Or you could go out by yourself even to a half-block-long empty lot, into the bushes:

like a creature of leaves you’d lurk, crouched, crawling, simplified, savage, alone;

already there was wanting to be simpler, wanting when they called you, never to go back.

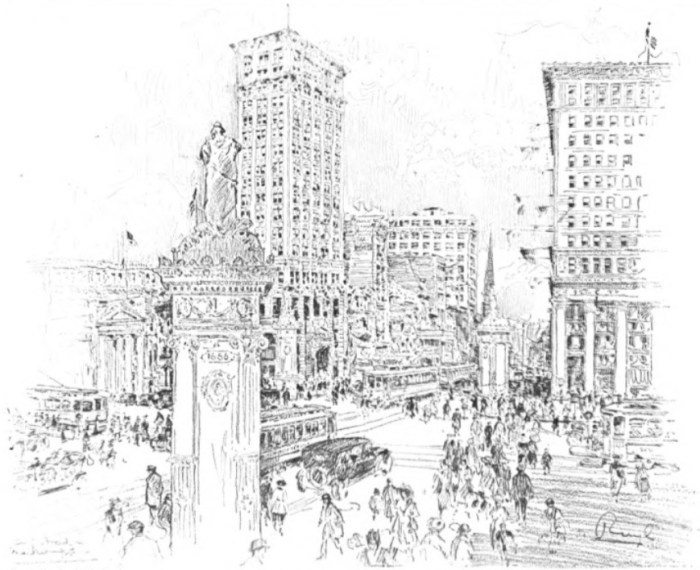

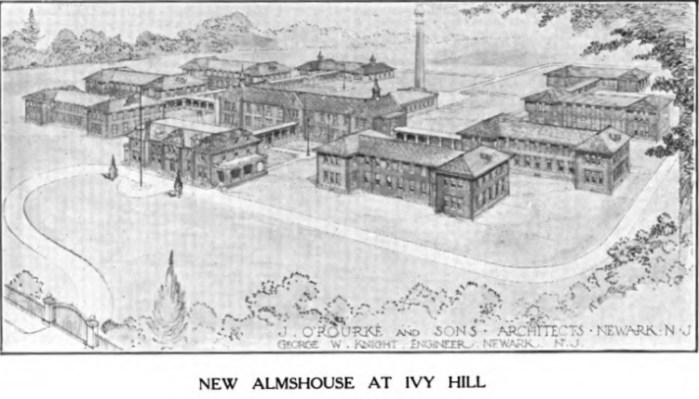

C. K. Williams was born and spent his boyhood in Newark. This poem, appearing in The Atlantic Monthly of June 1999, was also part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning collection Repair.